| |

|

|

The public utility industries function day by day largely un-noticed and unappreciated. Only when they become deranged in some way – through a burst water main, say, or a power cut – do we remember their vital importance. Reminders of their existence are, however, all around us if we are alert enough to seek them out. Many of the facilities exist within an invisible network of tunnels, subways and ducts beneath the roads and pavements of our cities and towns. The access points to this underground network are protected by strong metal covers so durable that some have lasted a century or more. Consequently the older ones may bear the names of long-defunct local authorities or utility companies, while the newest may be less informative.

This is the evidence which lies beneath our feet. Other examples of older street furniture are more visible: cattle troughs, perhaps, or direction signs. These, too, may have inscriptions identifying their original owners, or the name of the county council or former local authority which first put them there.

Brief histories of the principal public utilities operating in the London area are given below to assist in identifying these and other items of street furniture as they are found.

Note: most of the local government dates shown in this website have been checked against Frederic A Youngs, Jr, Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Volume 1: Southern England (Royal Historical Society, London, 1979). The remaining dates have been checked against the appropriate volume of the Victoria History of the Counties of England.

|

In simpler times young people were encouraged to take an interest in their surroundings, just for the pleasure of it. A series of these booklets was published by Big Chief I-Spy [Arnold Cawthrow], and this one is from 1961. The back cover lists others available at the time. [5x4 inches (130x100mm)] |

| |

WATER SUPPLY SERVICES

(i) Water Management

For many centuries London was supplied with water from a number of private companies which in 1856 comprised the following:

North side of the Thames

The New River Company (founded 1619)

The Chelsea Waterworks Company (1723)

The West Middlesex Waterworks Company (1806)

The East London Waterworks Company (1807)

The Grand Junction Waterworks Company (1811)

South side of the Thames

The Lambeth Waterworks Company (1785)

The Kent Waterworks Company (1809)

The Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company (1845)

At that time piped water in the home was enjoyed by only a minority, poorer people having to use a standpipe in the street (which might be turned on for only a few hours a day) or by obtaining their water from a well.

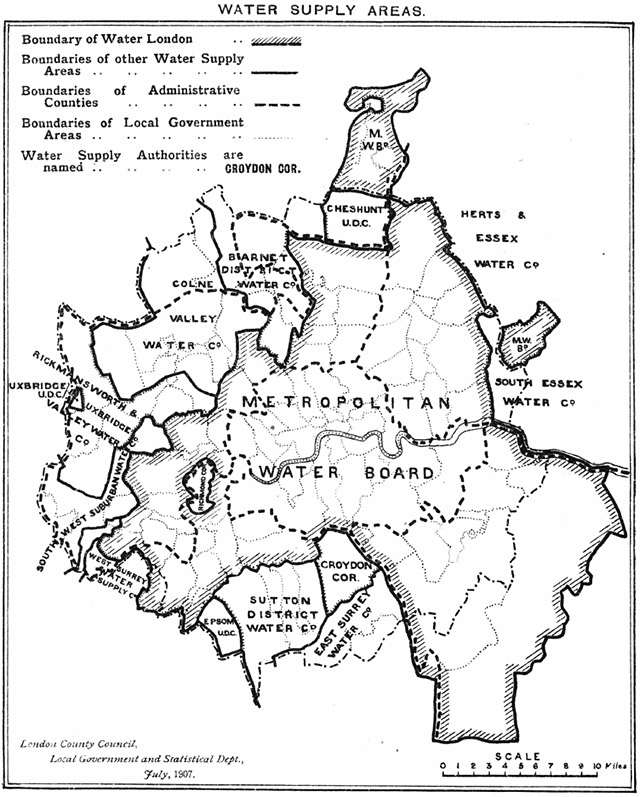

In the second half of the nineteenth century Parliament imposed increasing control over the management of the companies and there was continued clamour for their amalgamation into a single body, especially after the creation of the London County Council in 1889. Eventually a London Water Bill was introduced into Parliament in the 1902 session. This received Royal Assent as the Metropolis Water Act on 18th December 1902. It allowed for the creation of a Metropolitan Water Board (MWB) which had powers to take over the London water companies. On the ‘appointed day’, 24th June 1904, all were taken over except for the New River Company which followed on 25th July 1904. The MWB’s area stretched from Ware in the north; Sunbury on Thames in the west; Sevenoaks Rural District in the south; and Ilford and Chigwell in the east. Beyond the MWB boundary water supply was in the hands of a number of municipal bodies and private companies.

|

Source: London Statistics Vol XVII, 1906-7 (London County Council, 1907) |

| |

The MWB remained London’s principal supplier until the Water Act 1973 became law. This created, from 1st April 1974, ten regional water authorities for the whole of the UK which also took responsibility for rivers, drainage and sewage management. In London this was the Thames Water Authority (TWA). The TWA was part-privatized under the terms of the Water Act 1989 to become the publicly-quoted company Thames Water, while regulatory functions were devolved to a newly-created National Rivers Authority. |

|

Covers from the Metropolitan Water Board and the Thames Water Authority can be readily found. |

| |

(ii) Water Distribution

Water supply valve boxes may show a variety of initials indicating their function. Not all have yet been elucidated but the following may be noted.

| |

V |

Valve |

| |

A-V |

Air Valve |

| |

H-V |

Hydrant Valve |

| |

B-P |

By-pass Valve |

| |

E-V |

Emptying Valve |

| |

F-S |

Fire Supply valve |

| |

D-V |

Divisional Valve |

| |

D-M |

Deacon Meter valve (a Deacon Meter measures the flow of water through a pipe and detects and localizes leakages graphically.) |

| |

|

|

| |

Source: Big Chief I-Spy [Arnold Cawthrow], I-Spy On The Pavement (London, 1961) |

|

| |

(iii) Fire Hydrants

The provision of water facilities to fight fires was for long in the hands of private companies or, increasingly in the later nineteenth century, local authorities. In built-up areas water mains have provision for standpipes to be inserted at frequent intervals along most roads and streets into which the fire brigade’s hoses can be attached. These are now generally known as Fire Hydrants though other names such as Fire Plug were once used. The hydrants are constructed to standard dimensions. Older covers often bear the name of the local authority which was originally responsible for the provision of the hydrants in their area and they sometimes bear a year of manufacture too. The design of fire hydrants has changed in recent years; they are now shorter in length and the covers may have 45-degree chamfered corners at one end. They are also coloured yellow. The older size covers are no longer made so whenever older hydrants are reconstructed Thames Water in London retains the covers wherever possible so that spares are available whenever covers become broken. For this reason the local authority name on the hydrant cover may not be the district where it is now located. |

|

Two variants of newer style covers. |

| |

Ever since 1707 there has been a legal requirement for hydrants to be indicated by signs. At the present time the most familiar sign is the yellow ‘H’ plate fixed to a wall or small post nearby. On older signs the upper figure is the diameter of the pipe in inches and the lower figure the distance to the hydrant in feet; on newer signs the upper figure is the diameter in millimetres and the lower, the distance in metres. Unfortunately such signs are neglected and many are now missing, often through the construction of front-garden car parks involving the demolition of garden walls. Newer covers are usually coloured yellow, while older ones have sometimes had yellow paint rather hastily applied to them, perhaps to make up for the absence of a hydrant plate. |

|

A 4-inch diameter pipe 3 feet away. Plates are can be fixed in a variety of ways, some examples of which might be: on their own free-standing post, strapped to a lamppost or, as here, screwed to a wall. [courtesy of John Liffen] |

| |

|

A 100mm diameter pipe 1 metre away. [courtesy of John Liffen] |

| |

An earlier type of Hydrant marker, as seen on the right here, can still be found, though they are by no means common.

[courtesy of John Liffen] |

|

|

|

| |

(iv) Cattle Troughs

In the nineteenth century increasing concern in London for the provision of clean drinking water led to the foundation of the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association in 1859. It expanded its remit to include cattle troughs in 1867, though horses were probably the principal beneficiaries. Its new name, the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain & Cattle Trough Association, was prominently engraved on all the Association’s troughs and drinking fountains. They became a widespread and familiar sight across London but gradually diminished in number during the later twentieth century as horse-drawn transport declined, through road-widening schemes and (sometimes) theft. The organization changed its name at an unknown date to the Drinking Fountain Association. |

|

Several of these survive in London and their use now as decorative flower planters is not unusual. |

| |

|

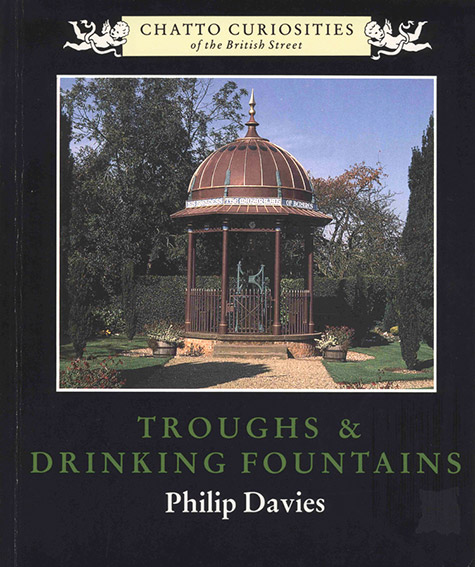

Philip Davies, Troughs & Drinking Fountains, Fountains of Life (London, 1989), is a useful historical survey of the subject, with London covered in particular detail.

[240x200mm] |

| |

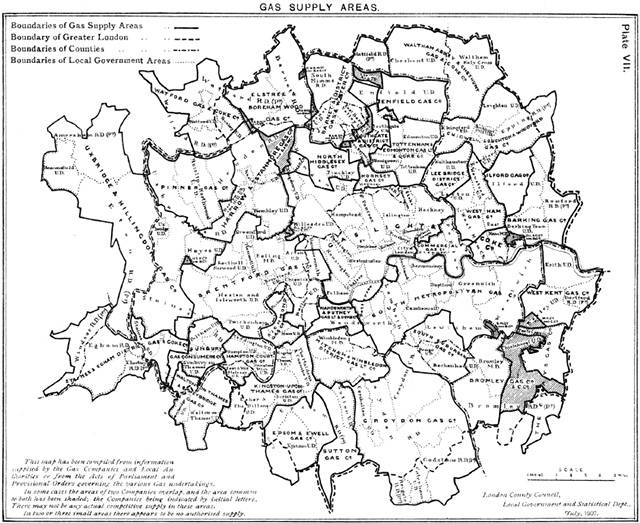

GAS SUPPLY

Coal gas began to be used for lighting purposes towards the end of the eighteenth century. In London the Gas Light & Coke Company was founded in 1810 (chartered in 1812) and from this time gas mains began to be constructed across the capital. By the middle of the nineteenth century gas was also being used for cooking and heating but it retained its supremacy as a source of lighting until the gradual spread of electricity supply from the 1890s onwards. The invention of the incandescent gas mantle in 1887, and its improvement in 1903, gave a boost to gas lighting but by the middle of the twentieth century this use of gas had largely been superseded. In the early years there was a large number of gas companies in and around London supplying only their own local areas but mergers gradually reduced the total. In 1938 the principal gas companies in the County of London were: |

North of the Thames

The Gas Light & Coke Company (founded 1810)

The Commercial Gas Company (1847)

South of the Thames

The South Metropolitan Gas Company (1842)

The South Suburban Gas Company (1858)

The Wandsworth & District Gas Company (1856) |

|

Source: London Statistics Vol XVII, 1906-7 (London County Council, 1907) |

| |

Beyond the LCC area there were still many local companies but they were all absorbed when the industry was nationalized by means of the Gas Act 1948 (vesting day, 1st April 1949). Twelve regional gas boards were created across the UK, those serving London being the Eastern Gas Board, North Thames Gas Board and the South Eastern Gas Board. The industry received a fillip when North Sea Gas was discovered in 1965, and Britain was progressively converted from town gas to natural gas between 1968 and 1976. The industry was privatized in 1986 with the formation of British Gas PLC. |

| |

ELECTRICITY SUPPLY

In Britain the first steps towards the provision of electricity supply came in the late 1870s with a few experimental electric lighting installations. What were probably the first public power stations in the world, albeit on a minuscule scale, were those at Godalming in Surrey in 1881 and Holborn Viaduct in April 1882, though neither of these lasted very long. The first legislation dealing with electricity supply was the Electric Lighting Act of 1882 but the technology was not developed enough and investors felt cautious. In 1888 another Electric Lighting Act received Royal Assent with slightly more lenient provisions. With the prospect of more reliable generating equipment and greater demand being evident more investment was forthcoming. Initially private companies had the field to themselves but before long the more enterprising municipalities joined in, especially where this enabled competition with a local private gas company.

The development of public electricity supply in London has been covered by the late M A C Horne in his ‘Metadyne’ website, http://www.metadyne.co.uk/Power.html, and readers are referred there for full details. Supply continued from both statutory companies and local authorities until nationalization of the industry under the terms of the Electricity Act 1947 (vesting day, 1st April 1948). The industry was privatized by means of the Electricity Act 1989 (vesting day 31st March 1990). The functions of the Central Electricity Generating Board were divided into three new companies, PowerGen, National Power and National Grid Company. The twelve area electricity boards were vested in independent regional electricity companies. Changes since then are beyond the scope of this brief survey.

Note: On this website a date span is shown for the existence of each local authority. Where such authorities were responsible for the supply of electricity in their district, the dates shown do not necessarily represent the whole period during which the supply was given. For example, the Metropolitan Borough of Hammersmith was in existence between 1900 and 1965 and pavement covers are found with the initials ‘H.B.E.D.’ (Hammersmith Borough Electricity Department), see H&F001 and H&F002. However, electricity supply was begun by its predecessor, Hammersmith Vestry, in 1907 from its power station at 85 Fulham Palace Road and supply was continued by Hammersmith Borough Council from 1900 when it took over from the Vestry. The council in turn relinquished ownership to the British Electricity Authority at the time of nationalization in 1948 but the power station, several times enlarged over the years, continued to generate electricity until 17 March 1966, though by then feeding into the National Grid rather than providing a purely local supply. |

| |

TELECOMMUNICATIONS

(i) Electric Telegraph Service

The first statutory company for the provision of inland public electric telegraphy in Britain was the Electric Telegraph Company, incorporated in 1846. Competing companies soon emerged, among them the British Electric Telegraph Company (1850) and the English & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company (1851). These amalgamated in 1856 to form the British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company. The last major inland company to be formed, the United Kingdom Telegraph Company, was also incorporated in 1851. Two London local companies were also formed, the London District Telegraph Company (1859) and the Universal Private Telegraph Company (1860), both utilizing over-house distribution wires. Virtually no evidence of the infrastructure of any of these companies now survives. In 1870 the inland telegraph companies were nationalized and their operations taken over by the General Post Office (GPO).

(ii) Telephone Service

The telephone was introduced to Britain in 1878 but the GPO had only a small involvement with telephone development for most of the nineteenth century. Instead they licensed a number of commercial companies to provide telephone services. In 1889 the three largest such companies, the National Telephone Company, the United Telephone Company and the Lancashire & Cheshire Telephonic Exchange Company, merged to form an enlarged National Telephone Company (NTC).

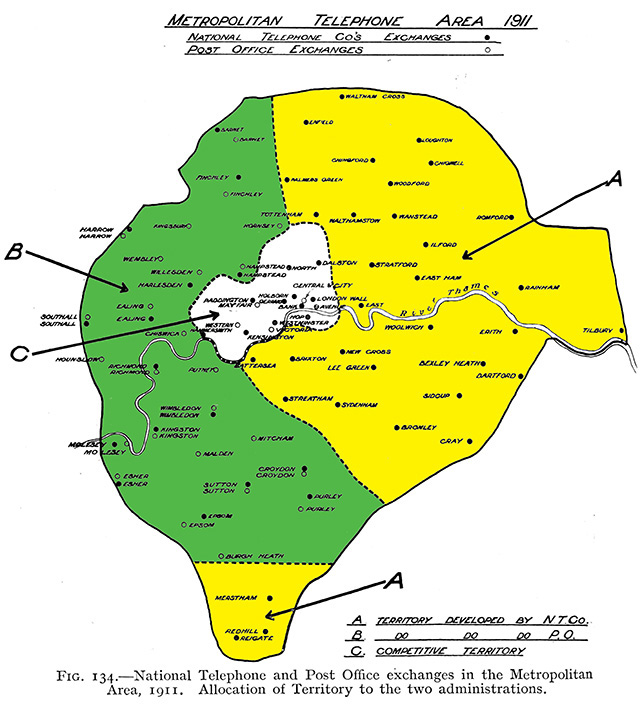

In 1901 the British government obliged the NTC in London to accept the GPO as a telephone competitor. For administrative purposes London was divided into three zones. The Green zone was the western half of the Greater London area, Yellow, the eastern half, and White, inner London. The GPO took Green, the NTC, Yellow, while both competed within the White. In the Green zone the NTC continued to maintain its existing network but could not expand it. |

|

The Yellow zone is represented here by ‘A’ (NTC), the Green ‘B’ (GPO), with ‘C’ being the white area where they would compete.

Source: F G C Baldwin, The History of the Telephone in the United Kingdom (London, 1925). [The original map was black & white – coloured here for clarity.] |

| |

The GPO, as a government department, had the authority to break up the roads for underground ducts and will have done so from 1870 onwards. The NTC, however, was legally obliged to negotiate wayleaves from all landowners in order to construct underground ducts (the NTC frequently petitioned the government to get this restricting legislation amended). For this reason much of its distribution network was by means of overhead poles and wires. The existence of pavement ducts from the NTC era will be evidence that permission had been successfully negotiated in a particular district but this will be hard to confirm unless NTC joint-box covers are actually found. Even then caution should be exercised as it cannot be certain that covers are still in their original location. Probably the majority of telephone ducts and joint boxes in London date from 1901 onwards. The NTC came to an end on 31st December 1911 when its licence expired and its entire organization and infrastructure were purchased by the GPO.

The development from the early 1930s of ‘voice-frequency telegraphy’ (in other words, using alternating currents similar to telephone signals) reduced the distinction between telegraph and telephone circuits. Why the GPO had so many joint-box covers marked for telegraphs is not known but their indiscriminate use along telephone ducts is evidence of probable re-use of such items recovered from other sites.

The GPO ceased to be a government department in 1969 to become a public corporation, so the initials GPO were no longer used and the post of Postmaster-General was abolished (there was instead a Minister of Posts and Telecommunications). The Post Office was split into separate postal and telecommunications businesses in 1981 and telecoms was privatized in 1984.

In recent years cable subways and ducts constructed for electric traction purposes, for example power distribution for first-generation electric tramways or, later, trolleybuses, may have been re-used by telecommunications companies for their cables. |

| |

| < back to the main Street Furniture page |

| |

| * * * |

| |

|

|